Germophobes, beware: This article describes the unavoidable nastiness on your hands. Read at your own risk.

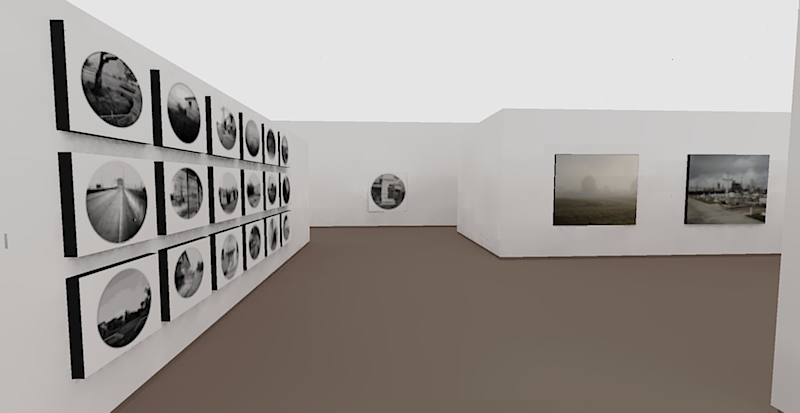

Sometimes, art is so beautiful, you can't help falling in love. Like the sirens' song, these pieces call to you: “Come closer. Look at my beauty. Reach out and touch me, just a little bit.” Subconsciously, your hand extends, and then a Museum security guard appears.

“Please don't touch the artwork,” the security guard warns.

Now you feel a small amount of shame and embarrassment. Things get awkward because you were reprimanded for doing something you knew you shouldn't be doing.

You probably know you're not supposed to touch the artwork in museums, but do you know the reasons why? Let's look at what happens to artwork when the temptation to touch overtakes you.

One of the objects in MOCA Jacksonville's Permanent Collection has some very distinct fingerprints etched permanently into its shiny mirrored finish.

First, we need to talk about how dirty you are. That's right, you're a dirty person. In fact, we all are. Humans can't help but be dirty. Why else would we take showers, wash our hands, or brush our teeth? Your skin does an amazing job at keeping this dirtiness on the outside of your body, but that means whenever you touch something you are going to leave some of that nasty behind. Exactly how nasty is your hand? Well, that's really up to you. Your skin has a sponge-like property that picks up trace materials from anything you have touched since your last hand wash. Your skin is as dirty as you make it. Even if you wash your hands more often than not, you still have some naturally occurring “bleh” on your skin. Your “fingerprint,” the residue you deposit from your fingers, naturally comprises three things: eccrine sweat, sebaceous oils, and dead skin cells. All three negatively interact with artworks.

Let's talk about works on paper, such as photographs, collage involving paper, and any form of prints (lithographs, etchings, screen prints, etc.). Paper is naturally absorbent, which is why printing ink sticks so well to it. Even in photographs, the gelatinized silver nitrate adheres to the fibers in the paper. Paper, however, cannot choose what materials it absorbs; it absorbs everything that comes in contact with it. So when you touch a piece of paper with your bare hand, the paper will suck up whatever is on your fingers. The worst offender here is sebaceous oil. This grime will, over time, discolor the paper and allow more dirt to stick to it as well. Have you ever looked at your napkin after eating fried chicken? It's the same principle, just on a smaller scale.

By touching some paintings, you could accidentally remove whole chunks of paint.

What about paintings? Paintings can use different bases, such as canvas, board, or metal. How does your hand affect these? Canvas is a lot like paper-absorbent-so the same rules apply. Bases like board and metal are more resilient to your griminess, but the paint itself is not. Paintings are typically coated in a varnish to help stabilize the paint; when you touch them, your fingerprints chemically alter the varnish in those very spots. These spots begin to turn dark and cloudy and even attract dirt from the surrounding environment. This will ruin the original color of the paint. If the dirt you leave behind doesn't hurt them, your brute force could damage the art as well. In the case of thick impasto paintings, you could accidentally remove a whole chunk of paint. I've even seen some people pick at paintings, as if they are actually trying to remove the paint! The nerve!

But sculptures must be so stable that surely you can touch them, right? If you've read this far, you already know the answer. If the sculpture is made of metal, then your finger can do irreparable damage. The real culprit here is eccrine sweat. Keep in mind that sweat is one of your body's waste products. Human sweat differs from person to person but is always loaded with all kinds of acids like acetic, uric, lactic, and amino. If you have visited the Rock Paper Scissors exhibition or have a background in printmaking, you know that acids corrode and etch metal, a desired effect in printmaking but not in other forms of art that include metal. One of the objects in MOCA's Permanent Collection has some very distinct fingerprints etched permanently into its shiny mirrored finish.

However, it's not always about what your fingers leave on a piece. When you touch anything, you will remove trace elements from the surface. This lightly polishes the area you just touched. This part of a sculpture will not age the same way as the rest of the piece, and can even wear down. Have you ever seen a sculpture with a really smooth spot that is a lighter color than the rest of the piece? That's because people are touching it. In Verona, Italy, a famous sculpture of Juliet, the tragic, star-crossed lover from William Shakespeare's play, had to be removed because the right breast was starting to deteriorate. Somehow, it became a tradition for tourists to touch this breast for good luck. People are weird.

In conclusion, folks: DON'T TOUCH THINGS. You've always known this rule, and now you know why. The risk of you damaging the art is far greater than the reward of touching something. Please keep this in mind the next time you are tempted to put your dirty hand on that pretty piece of art.

The statue of William Shakespeare’s Juliet in Verona, Italy, has been damaged from continued touching by tourists seeking luck in love. Image courtesy of Flickr user SteFou!