Yes. Yes, you may touch that, but only if you are an art installer (and you're wearing gloves). Have you ever seen a work of art that looks really heavy, complicated, dangerous, etc.? Have you ever wondered how it got there, or how it even made it inside the building? Who moves this stuff?

We do.

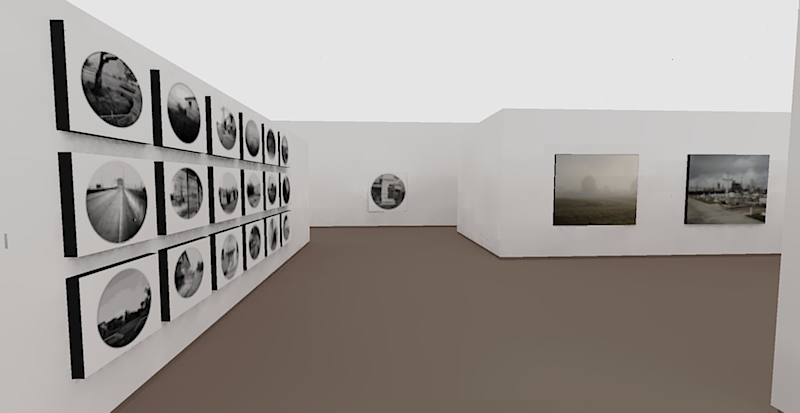

Art installers have the privilege/curse of physically putting together the exhibitions that you see when you come to MOCA Jacksonville. And we need a wide range of skills.

FOCUS ON THE DETAILS

Often we are asked to report on the incoming or outgoing condition of the works for an exhibition. This requires very detailed notes involving any visible marks, damage, imperfections, etc., that we can see on the piece. We do this to make sure that nothing changed on the artwork during the time that it was on display at the Museum. When I say “detailed,” I mean detailed.

This is a real installer conversation:

“So there is a mark that is noted at 3½ inches from the bottom and 17 inches from the left on the face of the canvas. Is it an abrasion or an accretion?”

“Definitely an accretion.”

Go ahead, look that word up. You can be the nerd that drops it at the next party and confuses everyone.

DO YOU EVEN LIFT, BRO?

Not all art is created equally, and a lot of times it's EXTRA HEAVY. Some works of art really benefit from being large, like Abstract Expressionist paintings. Some works depend on a heavy weight in the right spot so that they don't fall over at the slightest breath. Some works are made from materials you wouldn't expect, like faux cardboard boxes made of solid bronze (yup, that's real). All of this stuff can be pretty hard to move around, not to mention hang on the wall. We do use certain tools or machines to help us get these pieces to the right spot, but at the end of the day somebody had to pick that sucker up. That was the installers.

ATTACH FLAT PANEL (A) TO POST (B) USING MOUNTING SLEEVE (R) WITH SET SCREWS (J)

“Where the heck are set screws (J)? I don't think they were in this box!”

You might be surprised to learn that a lot of the works that end up in the gallery do not start out as one complete piece but instead come in a lot of small pieces. Sculptures are notorious for this. This is part of the reason that we are called “installers.” We receive installation instructions from artists whose work must be assembled on site. This is a regular practice and is almost always safer for the art in the long run. It's kind of like putting together furniture with all the crazy bolts and piece-except way weirder. For instance, I once received instructions that told me how to mount two turtle heads to a turtle body and where exactly to put the lobster made from traffic cones on his back.

YOU CAN BUILD THAT, RIGHT?

Some exhibitions feature materials that require us to build parts in order to display them properly. So a good knowledge of carpentry and metalworking is crucial to our job. Angela Glajcar's Project Atrium installation Terforation required that we design and manufacture two additional I-beam “outriggers” in order to hang her sculpture at the correct angle. For The New York Times Magazine Photographsexhibition, we designed and built display tables for the presentation of printed magazine articles.

Art installers have a pretty interesting job. We get to do a lot of things that sound crazy-and make for some really good stories. I thoroughly enjoy it. Maybe installing art sounds interesting to you. Just be careful what you wish for: you might not always want to touch the art.